“I left my heart in San Francisco,” crooned Tony Bennett. I once left my cashcard in Llandudno. There is also an artistic tradition of people deliberately leaving things in art galleries.

“I left my heart in San Francisco,” crooned Tony Bennett. I once left my cashcard in Llandudno. There is also an artistic tradition of people deliberately leaving things in art galleries.

Duchamp perfected the objet trouvé, inventing the “ready-made” by exhibiting unaltered everyday objects designated as art. It’s less clear who if anyone invented the objet déposé, or objet abandonné, or whatever you might choose to call those works that are left in a gallery as a comment or as an intervention.

Banksy has crept into the Tate and National Gallery in disguise and covertly stuck to the walls a number of satirical works. Another kind of intervention found Brian Eno peeing into Duchamp’s urinal, which seems much more sympathetic than the idiot who went to jail for defacing a Rothko in the name of his own ‘artistic movement’ Yellowism. Curiously, of these three instances it is Banksy’s that isn’t vandalistic, in spite of the larger part of his canonical stencil works being strictly speaking acts of vandalism.

Banksy has crept into the Tate and National Gallery in disguise and covertly stuck to the walls a number of satirical works. Another kind of intervention found Brian Eno peeing into Duchamp’s urinal, which seems much more sympathetic than the idiot who went to jail for defacing a Rothko in the name of his own ‘artistic movement’ Yellowism. Curiously, of these three instances it is Banksy’s that isn’t vandalistic, in spite of the larger part of his canonical stencil works being strictly speaking acts of vandalism.

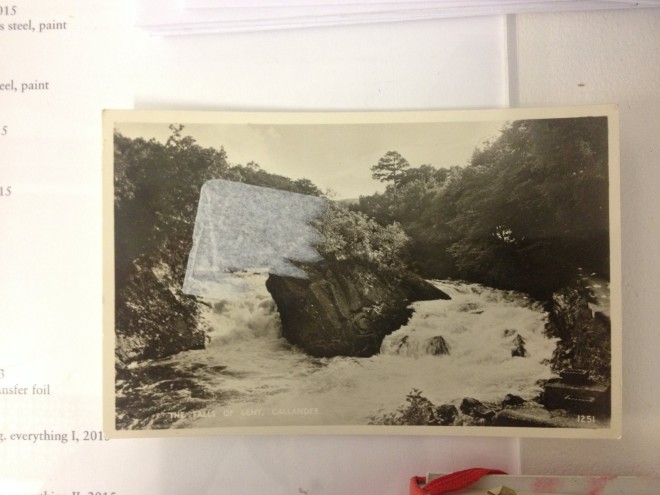

During Week 35 of Fig-2 someone left a postcard depicting “The Falls of Leny, Callander” though I’m still can’t quite convince myself it wasn’t actually part of the show. The rock formation within rushing water and an external overlaid shape left by a sticker perfectly matched the themes and techniques of the exhibition around it.

Amy Stephens uses sculpture, drawing and photography to explore relations between geological, architectonic and sculpted forms. She plays with the intersections between objects and how we represent objects. In her show two-dimensional representations turn into three-dimensional objects and vice versa via interventions in the forms by introducing synthetic elements to organic forms and organic elements to synthetic objects.

The room had been split into two exhibition spaces: one large and a smaller one in the corner which at first I missed. It was lucky they told me it was there because without the second room the show didn’t seem to work. Together the whole show suddenly came to life as the totality of the pieces resonated. The two-dimensional forms first encountered in the large space suddenly spring off the wall into full sculptural form in this second semi-hidden room. Considering all the works together let them ring out together like an orchestra. It was literally an object lesson in curation, and proof that the ‘art of curation’ isn’t just an amusing turn of phrase.

The room had been split into two exhibition spaces: one large and a smaller one in the corner which at first I missed. It was lucky they told me it was there because without the second room the show didn’t seem to work. Together the whole show suddenly came to life as the totality of the pieces resonated. The two-dimensional forms first encountered in the large space suddenly spring off the wall into full sculptural form in this second semi-hidden room. Considering all the works together let them ring out together like an orchestra. It was literally an object lesson in curation, and proof that the ‘art of curation’ isn’t just an amusing turn of phrase.

I loved the slippage between media, the way that a geometric shape would be presented in the big space on a photographic surface and then you’d find yourself confronting the same shape turned into a sculpture, the way the colours yellow, cyan and red would pass between sculptural objects, photographs and across the walls of the room.

I loved the slippage between media, the way that a geometric shape would be presented in the big space on a photographic surface and then you’d find yourself confronting the same shape turned into a sculpture, the way the colours yellow, cyan and red would pass between sculptural objects, photographs and across the walls of the room.

Solid and outline shapes in yellow overlaid the two silkscreens “Freeze-Thaw I & II”. A yellow line led along the length of a wall and continued inside a picture frame as if it had thrown itself off the wall, and finally found itself embodied in the yellow perspex lozenge of the spindly-legged sculpture teasingly entitled Silence.

Solid and outline shapes in yellow overlaid the two silkscreens “Freeze-Thaw I & II”. A yellow line led along the length of a wall and continued inside a picture frame as if it had thrown itself off the wall, and finally found itself embodied in the yellow perspex lozenge of the spindly-legged sculpture teasingly entitled Silence.

The same thing happened with the blue waterfall roll of heat transfer foil “The First Dive” spilling back into the blue shape digitally overlaid over the rock form photography in the c-prints “Rock-fall I & II”.

The same thing happened with the blue waterfall roll of heat transfer foil “The First Dive” spilling back into the blue shape digitally overlaid over the rock form photography in the c-prints “Rock-fall I & II”.

The digitally overlaid blue shape then turns white and emerges as the flock-covered lozenge-on-legs sculpture “Tethered Object”, and the heat transfer foil reminds us through artificial means of the great violence of slow geological processes to shape valleys and mountains from solid rock.

The digitally overlaid blue shape then turns white and emerges as the flock-covered lozenge-on-legs sculpture “Tethered Object”, and the heat transfer foil reminds us through artificial means of the great violence of slow geological processes to shape valleys and mountains from solid rock.

The rocks emerge from the flat plane of photography into the gallery in the form of “something. anything. everything. I, II & III” in which there are three rocks. I tell a lie, they’re minerals. Jesus, Marie! They’re minerals! Specifically the mineral ilmenite, a weakly magnetic black and grey ore of titanium. These minerals have been wrapped in red tape: line interacting with shape, then the line wanders off and finds itself as a red flocked fabric line going up through clear Perspex in the large sculpture “Unicorn”, where it looks like either the broadly ascending line of a rising company or the descending fortunes of a failing one. What it is in fact is not dissimilar: it is a representation of the Palio horse race in Siena, Italy created through extreme simplification of a horse or a person stripped to essential forms and motifs.

The rocks emerge from the flat plane of photography into the gallery in the form of “something. anything. everything. I, II & III” in which there are three rocks. I tell a lie, they’re minerals. Jesus, Marie! They’re minerals! Specifically the mineral ilmenite, a weakly magnetic black and grey ore of titanium. These minerals have been wrapped in red tape: line interacting with shape, then the line wanders off and finds itself as a red flocked fabric line going up through clear Perspex in the large sculpture “Unicorn”, where it looks like either the broadly ascending line of a rising company or the descending fortunes of a failing one. What it is in fact is not dissimilar: it is a representation of the Palio horse race in Siena, Italy created through extreme simplification of a horse or a person stripped to essential forms and motifs.

“Unicorn” seems at first a curious title for it. Just like “Tethered Object”, it isn’t tethered, just as a unicorn can’t be tethered. Being mythical it either doesn’t exist or it exists as an absence (like silence, maybe even the yellow lozenge sculpture “Silence”). A unicorn is strong, being a beast, and fragile, in terms of its mythical rarity. Similarly the sculptures all possess this simultaneous stability and fragility. Untethered, you could knock them over easily, and people always walk into things.

“Unicorn” seems at first a curious title for it. Just like “Tethered Object”, it isn’t tethered, just as a unicorn can’t be tethered. Being mythical it either doesn’t exist or it exists as an absence (like silence, maybe even the yellow lozenge sculpture “Silence”). A unicorn is strong, being a beast, and fragile, in terms of its mythical rarity. Similarly the sculptures all possess this simultaneous stability and fragility. Untethered, you could knock them over easily, and people always walk into things.

Unicorn (Leocarno) is actually one of the seventeen contrade (city wards) that compete in the Palio di Siena, so we even find here slippage between language and form: the name unicorn becomes a thing unicorn (just as James Joyce had made a cork frame for a photo of Cork city). The emblems of the district are the same reddy-orange as the lines of “Unicorn” and “something. anything. everything”.

Unicorn (Leocarno) is actually one of the seventeen contrade (city wards) that compete in the Palio di Siena, so we even find here slippage between language and form: the name unicorn becomes a thing unicorn (just as James Joyce had made a cork frame for a photo of Cork city). The emblems of the district are the same reddy-orange as the lines of “Unicorn” and “something. anything. everything”.

Mention of Palio reminds me of a point raised by Douglas Hofstadter: Chi dice Siena dice Palio — to mention Siena is to bring up its famous horse race. Which would go for Wimbledon too: you think of tennis (or wombles?). In any word, many concepts are sous-entendus: there, but whispered. Inherent. A tethered object.

Even the striking rock and mineral forms in the photographs have been created by the eroding action of water: stable and fragile, hard and soft. “Tethered Object” looks inscrutable and monolithic, but its hardness is balanced by its spindly legs and its covering of flock, the lustrous velvety fabric that is Amy Stephens’s signature material. Flock draws the eye and light in: it’s soft but it’s also highly synthetic. Black flock is used like bark to wrap a piece of wood, giving it a synthetic but somehow warm edge.

Even the striking rock and mineral forms in the photographs have been created by the eroding action of water: stable and fragile, hard and soft. “Tethered Object” looks inscrutable and monolithic, but its hardness is balanced by its spindly legs and its covering of flock, the lustrous velvety fabric that is Amy Stephens’s signature material. Flock draws the eye and light in: it’s soft but it’s also highly synthetic. Black flock is used like bark to wrap a piece of wood, giving it a synthetic but somehow warm edge.

In “Birch In Space” we encounter a branch of Icelandic birch wood that has been cast in eight pieces and welded together and suspended from the ceiling: the shape is organic and natural but the material is metallic and synthetic and the suspension gives it a lightness that offsets the weight of the metal. The pitching of the one against the other characterises all of the work. The shape of the cast birch also echoes “Unicorn”.

In “Birch In Space” we encounter a branch of Icelandic birch wood that has been cast in eight pieces and welded together and suspended from the ceiling: the shape is organic and natural but the material is metallic and synthetic and the suspension gives it a lightness that offsets the weight of the metal. The pitching of the one against the other characterises all of the work. The shape of the cast birch also echoes “Unicorn”.

“Pulpit” shows a photo of a clifftop, a famous Norwegian tourist destination formed of ilmenite and rock. You can imagine Moses standing at the top and declaiming his

“Pulpit” shows a photo of a clifftop, a famous Norwegian tourist destination formed of ilmenite and rock. You can imagine Moses standing at the top and declaiming his fifteen ten commandments, telling us how to live our lives. The Tetragrammaton YHWH (Yahweh) is derived from the verb that means “to be”, “exist”, “become” or “come to pass”: another slippage between language and form, another unicorn: words cast in stone.

“The First Dive” is inspired by David Lynch’s book “Catching the big fish: meditation, consciousness and creativity” and the idea of diving in when creativity takes over: jumping in at the deep end and submerging oneself in that danger rather than remaining sat in the shallow end. You need to take risks to move on. Any act of life worth living is a naturally occurring artificial intervention.

“The First Dive” is inspired by David Lynch’s book “Catching the big fish: meditation, consciousness and creativity” and the idea of diving in when creativity takes over: jumping in at the deep end and submerging oneself in that danger rather than remaining sat in the shallow end. You need to take risks to move on. Any act of life worth living is a naturally occurring artificial intervention.

I found Amy Stephens’s work thrilling in the way it exchanged colours and shapes between natural and synthetic forms and between two- and three-dimensional realms. It’s like a daytime Nights At The Museum, as if the non-living things all come out and cause trouble in real life.

Causing trouble in real life is what artists tend to be good at, from Banksy’s interventions to Stephens’s more personal artistic challenges in developing her play with forms and materials, and so on to that troubling and mysterious postcard “The Falls of Leny, Callander” . . .

You can listen to the Fig-2 audio interview with Amy Stephens on Soundcloud